The amazing natural resources of the Delaware Estuary and its watershed — abundant finfish, shellfish, waterfowl, hardwood forests, cedar swamps, vast wetlands, diverse plant life, healthy topsoil, sand deposits and a complex network of streams, creeks and rivers — provided for the unique character and cultural landscape we now refer to as Down Jersey.

Today our connections to the resources may be less evident than they were a hundred or more years ago, but nevertheless, the people of the Bayshore depend on the environment and are defined by a deep-seated maritime heritage.

The Lenape were the first inhabitants to make use of the plentiful marine species of the Delaware Bay. They collected and smoked oysters, used their shells to make wampum, fished from log canoes and made use of beached whales.

Whales are what brought the first European settlers to the Delaware. New Englanders following the whales down the coast made first temporary, then permanent, settlements on the Cape May County shore of the Delaware Bay.

Following in the traditions started by the Lenape and adopted by the European settlers, the residents of the Delaware Bayshore have continued to take advantage of the incredibly rich and diverse maritime and marine resources of the Down Jersey Region. Visit the Down Jersey Region to see and experience the rich history that surrounds you.

Commercial Fishing

Commercial Fishing

Menhaden (also called bunker) were once the basis of the most important commercial fishery in New Jersey. They were harvested by ‘purse seine.’ A crew member climbed the ‘crow’s nest’ searching for a darkened patch of water indicating a large school of bunker. The small boats were then lowered from the mother ship to set the purse seine. Once the fish were netted, they were dipped into the hold of the mother ship and taken to a processing plant.

At the peak of the sturgeon fishery on the Delaware Bay, there were 400 individuals involved. Enough sturgeon were harvested to warrant a railroad line down the landing where they were brought in. Although their flesh was also utilized, sturgeon were predominately marketed for their roe, or eggs, which were processed into caviar.

Generation after generation of Bayshore inhabitants have waited with mounting excitement for the springtime return of the shad. This popular fish has permeated the culture, folklore and livelihood of the region as far back as we have records.

Today, rather than providing the mainstay to the local economies, some of these fisheries no longer exist and many are downsized significantly. Unfortunately, the decline of these fisheries is directly related to human activities. Pollution, overfishing, poor resource management and recreational fishing pressure have all contributed to the loss of our commercial fisheries.

Shipbuilding

Every Bayshore city and hamlet that had enough water to launch a boat had some shipbuilding activity. Jersey white oak was often used for both planking and framing stock; its availability allowed for the success of the shipbuilding industry. Atlantic white cedar, found in Bayshore cedar swamps, was often used for small boats and the decking on the larger vessels.

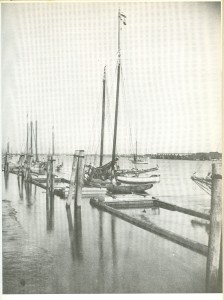

The earliest vessel type built at Delaware Bayshore shipyards was the sloop. It served a multitude of duties including catching oysters; transporting farm products, fish and shellfish, firewood and local goods from South Jersey to Philadelphia and nearby markets; and bringing home products not readily available to the rural communities along the Bayshore.

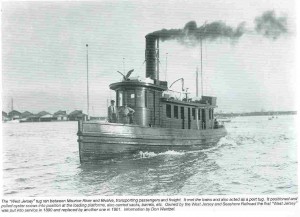

After the Civil War (approximately 1865–1885) there was a booming era of shipbuilding of a larger kind: coasting schooners. These three-, four-, and even five-masted vessels were used predominantly to carry lumber and coal, sometimes traveling as far north as Nova Scotia and as far south as the West Indies. Bridgeton, Mauricetown and Dennisville were the most productive area shipyards in the building of coasting schooners. Also built were tugs, scow schooners, mine sweepers, fishing boats and yachts.

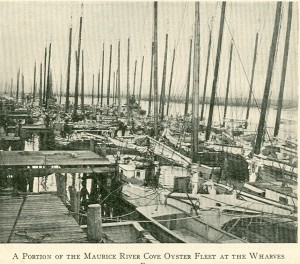

In numbers of vessels, Delaware Bay oyster schooners were most prolific. There were two distinct types, marking an evolution from sloop to small two-masted schooner to a large efficiently rigged oyster dredge boat. The design was adapted to the specific demands of the Bay’s prevailing conditions. At the peak of the oyster industry there were as many as 500 vessels licensed to harvest oysters from the Delaware Bay.

Oystering

The heyday of New Jersey’s oyster industry defined the Bayshore region of New Jersey. Oysters were the economic foundation  and a major influence on the way of life. In 1929, annual oyster sales were $6,000,000, invested capital was $15,000,000, and 4,500 people were employed for the Bay season with a weekly payroll of $112,000. Folklore has it that through the prosperity of the oyster industry, there were more millionaires per square mile in Port Norris than any other place in New Jersey — possibly in the entire nation!

and a major influence on the way of life. In 1929, annual oyster sales were $6,000,000, invested capital was $15,000,000, and 4,500 people were employed for the Bay season with a weekly payroll of $112,000. Folklore has it that through the prosperity of the oyster industry, there were more millionaires per square mile in Port Norris than any other place in New Jersey — possibly in the entire nation!

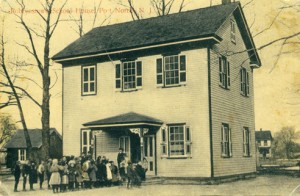

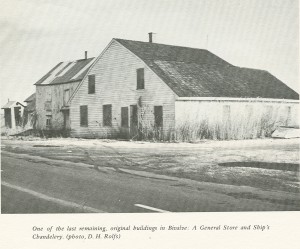

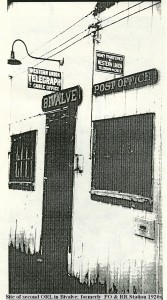

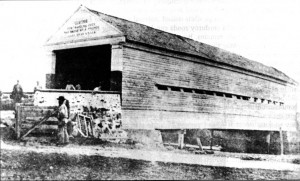

A series of shipping sheds, built by the railroad company and leased by individual oystermen (planters and packers) served to centralize the oyster industry in Bivalve. Everything needed to run the industry efficiently was housed in these segmented sheds along the Maurice River wharves. Included in the buildings were chandleries, meat markets, a post office, living quarters and office space. A smaller yet similar wharf was constructed on the Cohansey River — Greenwich Piers.

The industry fluctuated with major peaks and minor valleys from the late 1800s up until 1957 when it was hit by an epidemic disease known as MSX. Between 1957 and 1959 an estimated 90-95% of the marketable oysters in the lower bay died.

Although the industry has never fully recovered, there is today a viable oyster fishery providing a living for those few companies and oystermen who stuck it out through the tough times.

Water-based Recreation

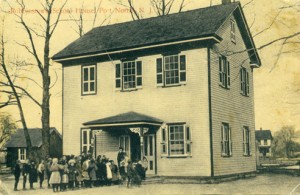

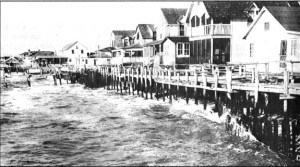

Several Delaware Bayshore towns were once popular summer vacation destinations. Sea Breeze had tourists arriving by steamer as well as turnpike and trolley to enjoy the bath houses, a boardwalk, billiards room, and even a bowling alley. Fortescue, the “Weakfish Capital of the World,” has long been a popular recreational fishing venue.

Hotels and restaurants provided the setting for enjoying the Bay’s resources. Biking, bathing, and excursions on pleasure crafts were just a few of the activities enjoyed by seasonal visitors.

Although many Bayshore people are still engaged in traditional maritime occupations, recreational pursuits on and around the water may now be the fastest growing use of the resources. ‘Ecotourism’ is on the rise on the Bayshore. Bird watching, canoeing, hiking, sailing and similar activities are growing in popularity as natural resource education, outreach and celebration become more prevalent. Still, these recreational activities don’t always create the stewardship that needs to be fostered. Teachers can help make the connection between natural resources and the products we all use in our daily lives, building a link between man and the natural world in which he lives.